Kriptografijo sestavlja tudi veja kriptoanalize. Kriptoanaliza se ukvarja z iskanjem šibkosti v kriptosistemih in pridobivanjem šifriranih informacij in tako imenovanim side-channel attack – om. To je način razbijanja šifer, ko se ne napade sistema direktno, ampak implementacijo in uporabo le tega.

Glavni cilj razbijanja kod in kriptoanalize je, da iz šifriranih informacij (ciphertext) pridobimo čim več podatkov, odkriti ključ in šifro ter tako priti do nešifriranih podatkov (plaintext).

Napade na kriptosisteme lahko razvrstimo glede na informacije, ki so na voljo napadalcu. Poznamo:

– Ciphertext-only: kriptoanalizator ima dostop samo do zbirke šifriranih besedil ali kodnih besedil.

– Known-plaintext: napadalec ima nabor šifriranih besedil, ki jim je znano ustrezno navadno besedilo.

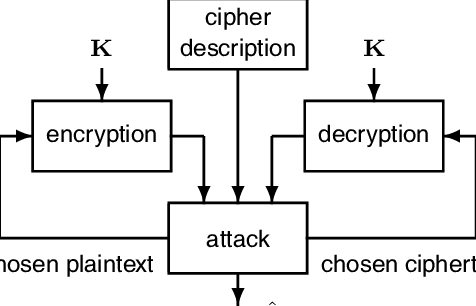

– Chosen-plaintext (chosen-ciphertext): napadalec lahko pridobi šifrirana besedila (navadna besedila), ki ustrezajo poljubnemu naboru navadnih besedil (šifriranih besedil) po lastni izbiri.

– Adaptive chosen-plaintext: tako kot napad izbranega navadnega besedila, razen da lahko napadalec izbere nadaljnje navadne besedila na podlagi informacij, pridobljenih iz prejšnjih šifriranj, podobno kot pri napadu izbranega šifriranega besedila.

– Related-key attack: Tako kot napad z izbranim besedilom, razen da lahko napadalec pridobi šifrirana besedila, šifrirana pod dvema različnima tipkama. Tipke niso znane, vendar je razmerje med njimi znano; na primer dve tipki, ki se razlikujeta v enem bitu.

Lahko jih razvstimo tudi po količini potrebnih sredstev, da razbijejo kripto sistem. Ta sredstva vključujejo:

-Čas – število računskih korakov (npr. Testnih šifriranj), ki jih je treba izvesti.

-Pomnilnik – količina pomnilnika, potrebna za izvedbo napada.

-Podatki – količina in vrsta plaintext-ov in ciphertext-ov, potrebnih za določen pristop.

Včasih je težko natančno napovedati te količine, še posebej, če napad ni praktično izvesti za testiranje. Toda akademski kriptoanalitiki po navadi zagotavljajo vsaj ocenjeno težavnost napada.

Poznamo dva načina šifriranja, simetrično in asimetrično šifriranje. Za simetrično šifriranje je značilno, da tako za šifriranje kot za dešifriranje uporabljamo isto metodo ali številko. Pri asimetričnem šifriranju pa za ta dva procesa uporabljamo različni metodi ali številki.

Od tega, ali je šifriranje simetrično ali asimetrično je odvisno tudi to, kako bomo šifro razbili. Pri simetričnem šifriranju je to dokaj preprosto, poznamo več različnih metod:

-Boomerang attack

-Brute-force attack

-Davies’ attack

-Differential cryptanalysis

-Impossible differential cryptanalysis

-Improbable differential cryptanalysis

-Integral cryptanalysis

-Linear cryptanalysis

-Meet-in-the-middle attack

-Mod-n cryptanalysis

-Related-key attack

-Sandwich attack

-Slide attack

-XSL attack

Asymmetric ciphers

Asymmetric cryptography (or public-key cryptography) is cryptography that relies on using two (mathematically related) keys; one private, and one public. Such ciphers invariably rely on “hard” mathematical problems as the basis of their security, so an obvious point of attack is to develop methods for solving the problem. The security of two-key cryptography depends on mathematical questions in a way that single-key cryptography generally does not, and conversely links cryptanalysis to wider mathematical research in a new way.[41]

Asymmetric schemes are designed around the (conjectured) difficulty of solving various mathematical problems. If an improved algorithm can be found to solve the problem, then the system is weakened. For example, the security of the Diffie–Hellman key exchange scheme depends on the difficulty of calculating the discrete logarithm. In 1983, Don Coppersmith found a faster way to find discrete logarithms (in certain groups), and thereby requiring cryptographers to use larger groups (or different types of groups). RSA’s security depends (in part) upon the difficulty of integer factorization — a breakthrough in factoring would impact the security of RSA.[citation needed]

In 1980, one could factor a difficult 50-digit number at an expense of 1012 elementary computer operations. By 1984 the state of the art in factoring algorithms had advanced to a point where a 75-digit number could be factored in 1012 operations. Advances in computing technology also meant that the operations could be performed much faster, too. Moore’s law predicts that computer speeds will continue to increase. Factoring techniques may continue to do so as well, but will most likely depend on mathematical insight and creativity, neither of which has ever been successfully predictable. 150-digit numbers of the kind once used in RSA have been factored. The effort was greater than above, but was not unreasonable on fast modern computers. By the start of the 21st century, 150-digit numbers were no longer considered a large enough key size for RSA. Numbers with several hundred digits were still considered too hard to factor in 2005, though methods will probably continue to improve over time, requiring key size to keep pace or other methods such as elliptic curve cryptography to be used.[citation needed]

Another distinguishing feature of asymmetric schemes is that, unlike attacks on symmetric cryptosystems, any cryptanalysis has the opportunity to make use of knowledge gained from the public key.[42]

Birthday attack

Hash function security summary

Rainbow table

Black-bag cryptanalysis

Man-in-the-middle attack

Power analysis

Replay attack

Rubber-hose cryptanalysis

Timing analysis